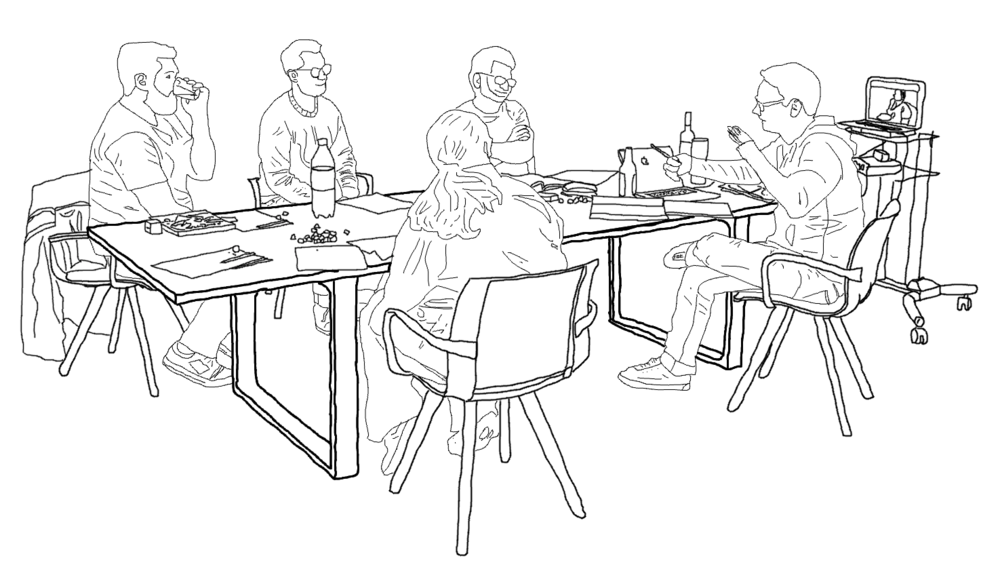

My enthusiasm for D&D caught on at work, mostly in the shape of curiosity. I was fielding questions like “but can I just say ‘and then I start flying up to a passing airship’?”. I suggested that I could run a game for everyone, and quite a few people said they’d like to come along.

The daunting challenge for me at this point was that I have never been a Dungeon Master before, and none of them have ever played before. Encouraged by the advice of literally every DM though, I decided to push ahead.

The first issue I wanted to tackle was writing an adventure. I’m a writer, so I figure I can do this. The writing went quite easily and quite well to start with. I asked for some advice from the reddit community and got some really good thoughts back. which lead me to tweak the story some.

Unfortunately, as the story tied up at the end, I didn’t like how it came out. The motivations of the NPCs seemed muddy, and so the moral choice for the players of man vs. nature wasn’t so clear. I like this story, and will continue writing it. However, it wouldn’t be done in time for the game at work.

I ventured out to look at the resources from the Dungeon Masters Guild. There’s a vast amount of content there, and with a bit of hunting around you can find exactly what you want. What I wanted was a one off game, which could be completed in a night, for 1st level players. I was in luck, and found Giantslayer. A whole adventure for just $1.95.

As a bonus treat, instead of reading through the adventure alone, I “played” the adventure with my partner as a solo adventure. Adjusting the combat a little on the fly, it went really well.

Using a premade adventure lifted a large amount of stress from the impending game. It was certainly the smart decision. As well as a verified one: other people had already played this game. I didn’t want to give the impression that D&D was too slap-dash just because of my inadequate writing. This adventure was a tried and tested one.

The other problem I wanted to tackle was some sheets in order to teach the players what they could do. I’ve completed the section on character creation, but the content is still quite long. I’ve also written the script to a video I want to produce telling new players about what D&D is, but video production is a lot of work, it turns out. Neither of these endeavours have been turned around in time for the game. Despite that, it didn’t seem like they mattered.

Instead of spending hours writing a helpful tutorial on how to create your first character, I should have simply turned to the premade characters. There’s quite a lot of them. Wizards have done a great job at putting the premade sheets together with enough information that a player with one knows quite well what their character can do. These sheets did much better than my 10 page document did. So long as you’re there to help out, a player with one of these premades doesn’t even need a Players Handbook.

So there you go. You don’t need to prepare very much to be a DM. The only required homework on my part was reading through the adventure, and then printing off a few premade characters… If you’re on the fence about starting an adventure, I’d recommend just doing it.

I’ll talk about how the actual game went shortly!