After recently playing Friday, a solo board game, I wanted to contrast the difference between how it gives rewards to players and how a game like Munchkin does. When the player tries something risky, how does that change the reward?

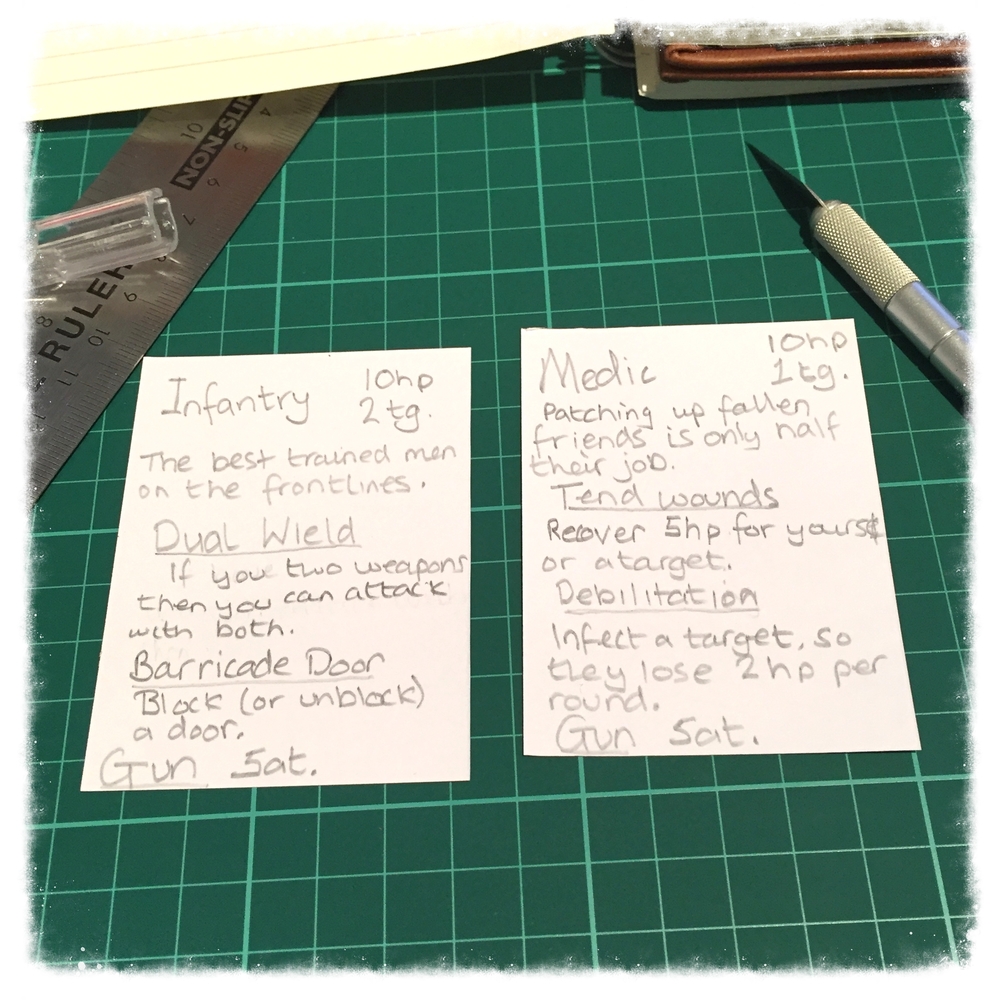

Friday is a single player game where you get to choose between two events to “fight”. The card is a great example of a dual purpose card: the top half is the hazard to succeed against, the bottom is the reward if you beat it. Although the two cards you choose from are still random (you could get two of the same card for instance) you still have the benefit of making an informed decision. You know that if you win, you’ll get this reward.

This makes the game much less “random”, opening the door to more skill. Now you can see the reward there’s a good amount of risk assessment you can do. You can contrast this with Munchkin. In Munchkin you flip a card to find your bad guy, and you attempt to fight it, completely unaware of how good the reward will be. Sure you can see how much treasures you could win, but you still might be risking your life for a pair of pantyhose you already own.

Having the event and the reward happen on the same card means you can tie them together thematically. Friday, unfortunately, doesn’t take advantage of this. Tying the reward to the card means you can make the reward more sensible: if you’re fighting a dragon maybe it makes sense to find dragon teeth and gold, but what would a direwolf be doing with those things?

Munchkin has no control over the rewards, other than saying the number. This makes it tricky to scale the rewards with the player progression in a game where that matters (not so much a thing in Munchkin). One of the upsides of this mechanic is that the reward can stay secret – something that doesn’t matter in a one player game like Friday, but is very important when you want to surprise your friends.