This weekend I’ve been thinking of interesting ways of doing combat in battles with various classes for an iPhone game.

Typically, you’ll find some kind of accuracy and mana combo. You can hit with you melee attack as much as you like, whilst your mana often runs out at some point. These are simple rules which are easy to keep track of for everyone involved (developers, GMs, players). However, they’re a bit samey. So lets forget about keeping things simple for the moment, and look for another way to manage these costs.

Master of Defence

This is the name I’m giving to the fighter class. The names comes from the people who wrote tomes of information regarding the subject back in the day, around the Medieval eras. These aren’t just sword wielding lunatics, but men (though, of course, the class shouldn’t be limited to men) who have been trained by Masters of the time before them.

The resource which a melee weapons fighter would be using up is their stamina. I like the idea of adding a cost to this – you try swinging a sword around for ten minutes and tell me you aren’t tired. My question here is how can we represent stamina without just giving it a number? (ie. Hey, you’ve got 62 Stamina left.)

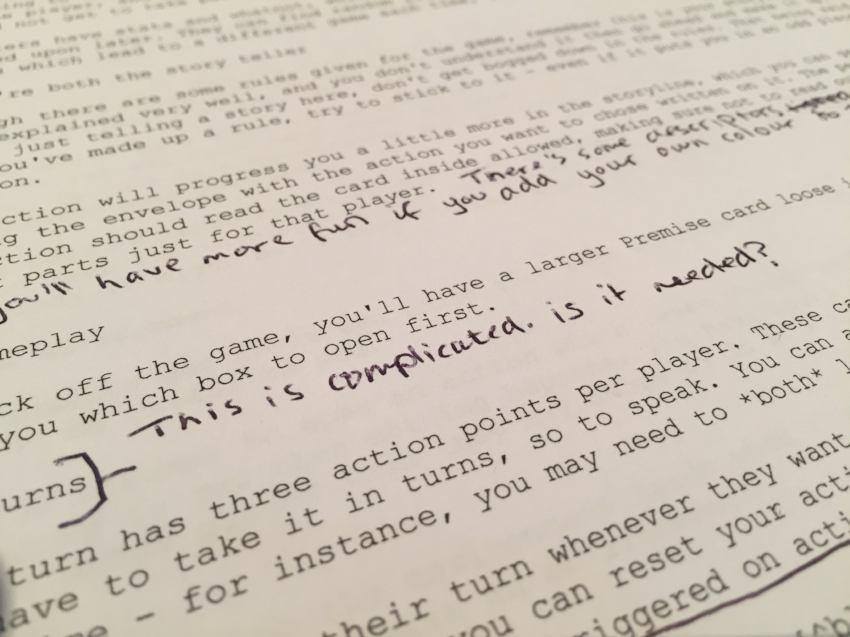

Listing actions, and general description of what the character is feeling. I’ve said looks here, but feels would be a better wording.

Listing actions, and general description of what the character is feeling. I’ve said looks here, but feels would be a better wording.

When fighting – in real life I mean – you’ve no idea how many punches you can throw before you get tired. I feel like in games we only get that feedback because that’s what is actually happening behind the scenes: there’s a counter somewhere saying 62 Stamina left and you’ve just used an 8 stamina parry so now you’ve got 54 Stamina left. This calculation is shown to you for some reason, possibly just by an accident of time. I want to hide that from the player. This’ll mean they will have to learn more about the character, and actually get to know their limits.

Once the character is out of stamina, they might pass out, or fumble and miss their turn. Maybe they try to swing their sword, but it hits meagrely. “You don’t have enough Stamina to pay for this ability” seems lazy to me. In D&D a fighter has superiority dice to use when trying to trip someone, but why? Can’t they just try to do it and hope for the best? Being tired doesn’t stop you doing something – it just stops you doing it well.

Without the numbers, we can use t-shirt sizes now. Lots of stamina, some stamina, little stamina. The cost can vary a little depending on how well the opponent parries or avoids the blow, and the feedback would be along the lines of “That hit really knocked the breath out of you!” rather than “That cost you 36.” Behinds the scenes we may need to track that number – that’s just how computers work – but outside you’d always be wondering how far you can push your hero.

A common way for deciding if an attack hits or not is usually based on accuracy of the attack vs. the foe’s defence. It’s a pretty decent way of doing it. I especially like how D&D 5e handles this: attacker rolls a d20 and adds on their proficiency and their strength (or dexterity) ability score. This number must be higher than the foe’s armour class. If it is, you’ve hit and can roll your damage dice. Otherwise, you’ve missed or the opponent managed to avoid damage thanks to their armour.

The d20 may be the most worrying part there, because it adds an element of frustrating luck. Using up all of your stamina on continual misses isn’t going to be fun – especially because a lot of the fun comes from physically rolling the dice. When you roll the dice, as dumb as it sounds, you feel responsible for the roll somehow. (People often change their dice after rolling badly once or twice.) To counter this we add more skill and less luck. The skill here should be knowing which attack does well against a particular foe. We should drop the d20 to a d6 (making it have less impact, but still allowing Lady Luck to smile upon you) and add a fixed bonus for the type of attack you choose. This bonus could be represented as “an astonishing blow!” or “the stone giant had no idea how to avoid that!”

The aim here to remove numbers from the player’s perspective – fighting isn’t about numbers – and encourage knowing the strengths and weaknesses of the specific hero when put against a specific mob. The player, just like if they were actually learning to fight with swords in the real outside, should feel benefits from practising with the character.

Channeler

This is a term I’m grabbing from Robert Jordan, and constitutes the spell caster class.

Mana is the common cost here, a boring number which counts down to zero when you’re “out of magic”. In Final Fantasy magic is (generally) just a number like this, and spells have a fixed costed assigned to them. In Dungeons and Dragons it’s quite similar, in that you have spell slots, and each spell has a slot “size” associated with it. I’m not sure anyone would think that’s how magic would work.

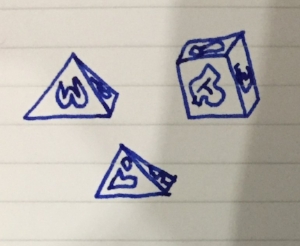

Very much hoping I can make this a story telling game – with words – rather than a reliance on images. I cannot draw.

Very much hoping I can make this a story telling game – with words – rather than a reliance on images. I cannot draw.

The way I would want it to work is that these people have a special connection to something. Maybe it’s another plain which they can send quick messages to, and then hope that something on the other side hears and is interested enough to help out. Who knows really, even the channelers aren’t sure. They just open their mind, say a few words of request, and then sometimes something happens. In this situation, I’m not sure why a finite number of requests is sensible. Channelers can keep talking into the void, the risk here (the constraining factor) is if anything from the other side responds.

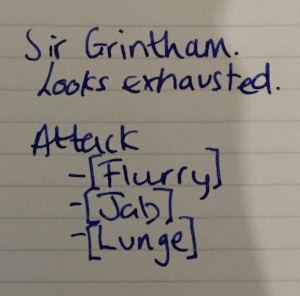

I really liked Neverwinter’s web-based side-game’s method of combat. (This has since been removed, due to killjoys breaking it.) In that, your character has a certain number of dice (maybe different types of dice too), which is tied to their ability. On these dice are symbols (boo, numbers): fire symbols, water symbols, necrotic symbols. The channeler’s specialisations would sway which symbols they may have. Similarly, a spell has a certain number of required symbols.

Say you want to cast the firebolt spell. It has a requirement of a fire symbol, obviously. Get just one fire symbol and the spell will work. Get six and the spell works brilliantly. Each turn, the character can cast as many spells as they like, so long as they’ve got dice to roll to try and cast them.

Of course, just rolling one fire symbol might not get you a very strong firebolt, but it would mean the likelihood of the spell going unanswered is low enough to keep it fun.

I would do away with ranged attack accuracy. This is magic, for fudge sake, you try dodging ethereal waves.

Deus Ex

These are people “of gods” who fill the role of clerics in other games. These people have the ability to hear and talk to the gods – something very few people have.

The currency these people dabble in isn’t mana or strength, it’s their god’s patience with them. In a world where gods are super powerful, but not necessarily omnipotent, having a nagging acolyte every few minutes could get frustrating. Whilst they’re not specifically bargaining with their god, they are asking for favours. And favours often come with a price.

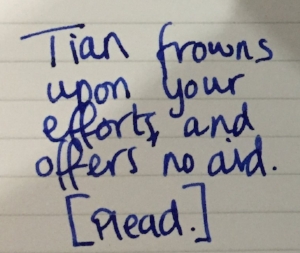

It’s not always the case that gods are happy with those that can talk to them.

It’s not always the case that gods are happy with those that can talk to them.

The interesting aspect of this class is that the “price” may not actually happen within the battle, and the price could vary depending on which god granted the favour to you in the first place. There some tasks a god may appreciate without having to ask for it specifically – prayer in an attempt to understand their true intent, or giving generously to those who are needing. However, from time to time a god may ask of a specific quest before they’ll give any more help. “I know you’re on your way east at the moment, but if you go out of your way north for half a day there’s something I want you to do in a small town there.” The player would have to sacrifice something – time, money, or gear – to keeping the god on their side.

Gods each have their own alignments, including more evil gods. Over time, these deus ex may find themselves strongly favoured by neutral gods but disliked by lawful good ones. The more renown with a particular god, the more likely they are to help you, and the better their help could be.

The consequence of not answering the call of a god might lead to them actively hindering your progress, or just turning their back on you.

This will stop greedy over-healing or too much taking advantage of having a hand of god on your side. Whereas before the consideration would be if you have enough mana left (which will soon regenerate), it now becomes concern over what the gods will ask of you. The cost may well be just, but is it worthwhile?

It might be important to remember here that the enemy probably has a god too, something which is forgotten in most other games. Whilst the gods often don’t interfere with the actions of the squishies on the ground, they certainly would step in if they thought another god was helping out too much. It might be interesting to have that come into play also, replacing the “accuracy” of a melee or ranged attack. Laito, the god who is most loved by the gnomes, has no interest in hurting them in your name.

Pact-Bound

Pact-Bound victims take the place of D&D’s warlocks. These are people have, for whatever reason, made a pact with some demon for great power. Of course now they find themselves in a contract they can’t get out of, not easily anyway.

Demons want only have one obsession: to take over the upper worlds, and break free of their otherworldly cells. The way they do this is by winning over the creatures who live in reality, and having them all decide the world is better with them running it. Pain and despair drive people to this awful conclusion, and so that’s what demons want in return. That’s the cost this character has to play with.

Along with their abilities is a pact cost, along the lines of “3 quarts of blood”. The deal is this: the demon will let you cast this spell, so long as some time soon, you can repay the demon 3 quarts of blood. If you can’t repay it, you give the blood yourself. These costs are likely steep. How are you going to get that much blood from this mimic beast? Do mimic’s even have blood?! Well, that’s something to worry about after this battle, I guess!

I enjoy this because it’s not a counter that you’re waiting to reset before you’re back at full working order. It’s a way of life for the hero. Sure, you could turn the opposite way and run from the approaching soldiers, but they do look like pretty full bloodsacks. Again, there’s no obvious number required here. The three in “3 quarts” seems like a real life measurement, not an arbitrary Integer in a memory block somewhere.

Poisoners

High profile assassinations in medieval times were rarely done with Assassin Creed like shadow dwellers. More often, the cause of death was slow and debilitating: poison. Inedible ingredients were easier to come by back then, and many people did a lot of study as to the ill affects they have on a person. The poisoner is a such a class.

I knew before I started that trying to draw that flower was ambitious…

I knew before I started that trying to draw that flower was ambitious…

The cost for a poisoner is the effort required to get the ingredients, and the time it takes to produce the potion. In a fight, this would be visible simply by listing the number of finished (or even half finished) poisons and potions that are available to hand. Outside of combat, the hero would spend some time looking for harpscorch flowers for their seeds, and swollen squirrel kidneys for the septic liquid that builds up inside them. They might mix these two together along with some simple cornflower to thicken it up, and let the brew sit for twelve hours. After that, they’ll have a perfectly good blight to smear onto their blade (or anyone’s blade that wants some).

Battle often comes at inopportune times though. After only six hours a bear charges out of the woods, and is running directly towards you. What affect would a six hour fermented blight have? Any? Should you waste the batch now to try it, or risk the battle without?

The brunt of a poisoner’s damage would come from over-time affects, like poison damage or making the enemy groggy for a few rounds. It introduces the tactic of guessing if it’s the right time to use a strong potion or a weak one. If a monster is only going to last one more round, maybe it’s not worth the ingredients to poison it.

So, like the Pact-Bound and Deus Ex, the costs here are found mostly outside of battle. They also seem more realistic.